These 8 lessons from psychology for your marketing team will help you understand better your customers and win more clients.

The economy is based on a rationally minded consumer. But the last few decades gave us sufficient insights that this is not always the case. On the contrary, consumers very often act irrationally.

From the ’80s and ’90s, psychologists are studying this phenomenon and provide more and more evidence of this. We have now many studies and theories explaining how consumers really behave and how companies can best understand them. However, despite the knowledge available, many businesses around the world still don’t apply many of these concepts that could drastically improve their performance.

In this article, we talk about 8 lessons from psychology for your marketing team to make your business more successful!

1. Prospect Theory

In 1992, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky developed the so-called prospect theory that got Kahneman a Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002. This theory states that people who can make money don’t take risks and people who can lose money are more likely to take risks. They run several experiments using different scenarios in which people could win or lose money.

To make it easier, let’s take this example:

- A: You have a 100% chance of winning € 100.

- B: You have a 50% chance to win €200 or 50% to end up with € 0.

In such a situation, most people seem to choose option A, because in option B they could potentially lose money.

However, if we take this scenario:

- A: You lose with 100% certainty € 100

- B: You have a 50% chance of losing €200 or 50% chance of no loss

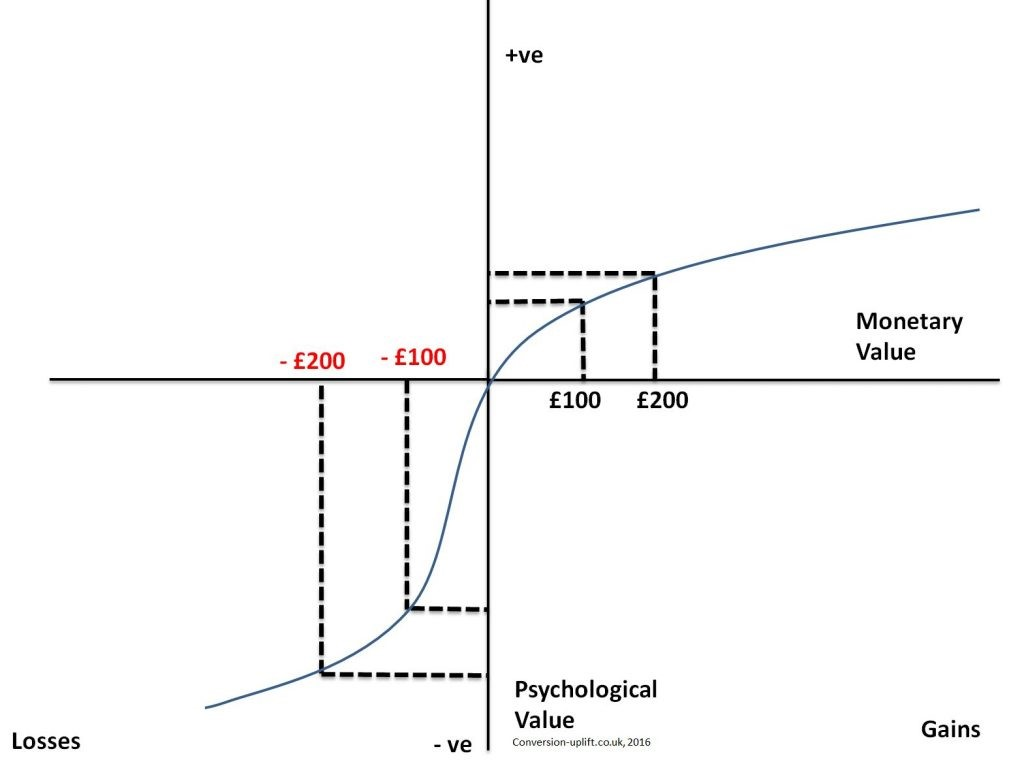

People mainly choose option B, in which they take the risk of losing 200 or nothing rather than losing 100 euros. The graph below shows why people act differently in both situations. On the x-axis, you can see the objective value (money), and on the y-axis the subjective value (how much value you attach to the amount).

The curve is steep at first and then decreases. As a result, we attach more value to an increase in our annual income from €20,000 to €40,000 than from €100,000 to €120,000 (the absolute value increases by the same amount).

The graph also shows that the extra value we attach to €200 compared to €100 is not twice as great. And is consequently not worth the risk of moving from 100% security to 50% security. In the loose situation, the average subjective value of €200 loss and no loss is better than the certainty of losing €100. In addition, the same graph shows that the curve in the negative domain remains longer steep than in the positive domain. This is because losses outweigh profits. The negative emotion we experience when losing €100 is comparatively stronger than the positive emotion we experience when winning €100.

So What Can Your Marketing Team Learn From This?

The first practical implication is that it’s a good idea to start creating experiences and value propositions that mainly focus on loss rather than gain. That’s what happens for example with subscription-based services. In these cases, the consumer is tempted to take a free trial because there is essentially no risk involved. What happens next is even more interesting, because after the free subscription has expired, people no longer want to live without it. Canceling the subscription feels like a loss.

We don’t want to experience this loss, so we choose to extend the free subscription or upgrade it.

2. Endowment Effect: We Don’t Want to Lose What We Own

The endowment effect means that we value our possessions more than the things we don’t own. This effect can also be explained with the prospect theory. If you can trade a product that you own for another product that is just as valuable, then we usually choose not to trade. Because we attach more value to our own possessions, an equal exchange actually feels like losing.

But how do you apply this if the consumer is looking for a product and does not own anything yet? This story makes it pretty clear.

When I was fourteen I went on a day trip with my family and sister and I was allowed to pick out a birthday present. Close to our home, there was a beautiful mountain bike path in the woods, so I decided that my gift would have been a brand new mountain bike. When I entered the bike shop, my eyes were immediately fixed on a metallic-grey Giant. After having pressed the brakes 25 times, the salesman asked me if I wanted to ride it for a test drive. I cycled 10 laps over the parking lot behind the shop and I was immediately sold. I found my bike!

By letting me hold the bike and take a test ride, I already considered it partly as my property, so I didn’t want to say goodbye to it anymore. That’s basically what car dealers do when they offer you to drive their newest cars.

The endowment effect (cherishing) also occurs in people with shares. Even when the values of shares are at a loss, people have trouble selling their shares. This is because we give a higher value to the shares we own.

3. Mental Accounting

Mental accounting is a process whereby economic results (profit or loss) are categorized and evaluated. Research by Thaler (1999) showed that in certain situations we prefer to add up profits and losses and in other situations, we prefer to process the amounts separately. Also, in this case, we can use the prospect theory to explain this concept. There are a few examples of situations to explain the preferences:

- A: You bought two lottery tickets. One won €50 and the other €25.

- B: You have won €75 with one lottery ticket.

In both situations, you win the same amount, but Thaler’s research shows that you tend to be happier in situation A. This effect can again be explained by means of the prospect theory. The graph of the prospect theory shows that the combined subjective value of €50 and €25 is higher than the subjective value of €75. In a loss situation:

- A: The tax authorities will tell you that you made a mistake in your tax return, you have to pay back €50. Then get another letter that you also have to pay back €25 over the previous year.

- B: You will receive one letter from the tax authorities stating that you have to pay €75. In this situation, we prefer option B, because the subjective value of an integrated amount is less negative than the two amounts to be paid.

The lesson you can learn from the first example is that you should separately name the ways of saving money by choosing your product. “If you choose product X, you will save €… on Y and €… on Z.”. If the focus is on making costs (example 2) then you need to integrate the costs: “For product X, you only have to pay €15 a month to pay for the device and the subscription.”

4. Disjunction Effect

Research by Shafir and Tversky shows that consumers have a strong preference for certainty. Often we only dare to make a choice when we are sure of something, even though the outcome is not relevant to the decision.

This was demonstrated by a study in which students were asked if they would go on a holiday to Hawaii if they had passed their exams. The result was that students said they would travel if they had passed their exams, but also if they had not. The students who didn’t know if they had passed the exam indicated they wouldn’t go on a trip. It is, of course, strange if your behavior is the same regardless of the outcome of your exam. So people value information that is not important for making the decision.

The influence of information is also reflected in the stock market. After the results of the American presidential elections, there is often a lot happening on the stock market. Even though many people strongly doubt that the results of the elections have any influence on the price of the stock market.

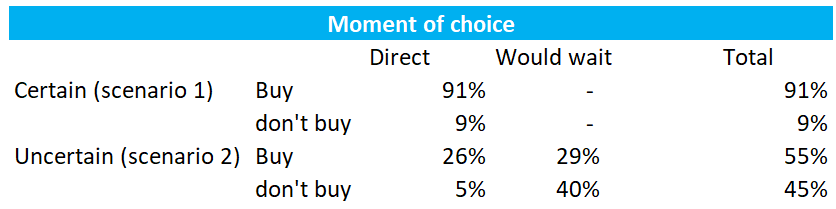

Bastardi and Shafir demonstrated the disjunction effect in a study in which people were shown one of the two scenarios below:

You recently decided to buy a new CD player and this week there is a 50% offer on the product you want. But the offer is only for today.

1. However, your amplifier is broken and the warranty has expired, the repair costs are €90. Are you buying a CD player?

2. Your amplifier is broken, but the repairman must first check the date of the warranty. You won’t know until tomorrow if the warranty is still valid, or if you will have to pay €90. Are you buying the CD player today?

Don’t you buy a CD player?

Or

Will you wait until tomorrow?

This table shows that in the second scenario, 69% ( 29% + 40%) of people chose to have the guarantee checked, and then 40% of the total number of people decided not to buy the CD player.

The result of the uncertainty was that 45% of the people did not buy the CD player, whereas that was only 9% in the scenario in which people had security. Basically, the disjunction effect shows that consumers who do not have all the information available. Even if this information doesn’t affect the decision, tend to be more indecisive.

Removing Customer Uncertainty

It is a complicated phenomenon to respond to because people tend to look for information that is not present. Of course, this can vary from person to person. My advice is, therefore, to be as open as possible to the customer and to offer the possibility to have customers ask questions in an easy and accessible way. But keep in mind that every strategy to remove uncertainties from the customer is beneficial in terms of the disjunction effect.

5. Choice-Overload: Can You Have Too Many Choices?

The ideology of our Western society is based on the fact that increasing our well-being is linked to increasing our freedom. After all, freedom is good, valuable and offers every individual the opportunity to act the way he or she wants to.

The way in which we increase individual freedom is to increase choice. As a result, the increasing choice has become linked to increasing our freedom. This is the line of thought of Barry Schwartz, whom he introduced in 2000 under the title The tyranny of Choice. Research by Iyengar and Lepper (2000) shows that more choice does not always lead to more satisfaction and willingness to buy.

People did show a strong preference for the possibility of having a lot of choices. The paradox, however, was that people with less choice made a purchase earlier and were more satisfied with their choice. Regret plays an important role in this because more alternatives increased the degree of regret.

6. Complex Novelty

Research by Noorderwier and Van Dijk looks at the communication of product innovations. Many companies introduce a new product to the market by labeling it as brand new. However, the researchers show that product innovations are more successful if they are presented as: “comparable to” or “works just like”.

People must have the idea that they can handle the product. If people have that, the interest in the product also increases.

7. Copycats

By copycats, we mean brands that try to benefit from the name and reputation of well-known brands. It is often a cheaper version of, for example, Coca-Cola or Starbucks.

Research by Pieters and Van Horen shows that people in an unfamiliar environment are more positive about copycats. They indicate that a Dutchman in Shanghai is more willing to go to a Starbucks copycat (Usabucks) than if it is in the Netherlands. So we have a preference for known in an unfamiliar environment. While in a familiar environment there is an aversion to copycats.

8. Evaluability Hypothesis

The evaluability hypothesis states that our evaluation of a product depends on the ability to compare the product. This was demonstrated by measuring people’s willingness to buy a product in two situations. Alone or together with the other product.

For example, people were given a choice between a dictionary with 10,000 words without defects or a dictionary with 20,000 words and a torn front. If the dictionaries were assessed separately, the majority opted for the 10,000-word dictionary. If the dictionaries could be compared, the majority opted for the 20,000 words dictionary.

This is because the number of words is a characteristic that is difficult to judge without an alternative. A dictionary with a torn front is always noticeable. An implication of this is that in the separate evaluation it is sometimes better to give less information (such as torn front). It may also be wise to give a percentage indication of the average in the separate evaluation. Think about it: “This processor performs 30% better than the average processor within this price range”.

What to Do With All This Research?

The aim of this story is to provide more insight into the irrationality of today’s consumers. Psychological research is often a tangle of situations to which effects are subject. The economy generally has little need for this because there are no formulas to stick to it. Only when it can be demonstrated that behavior is predictably irrational can it be used in the economic field.

The studies I have explained above show robust results that the consumer does not always act rationally. The predictability of irrationality makes it possible for the marketing and sales departments to respond to this. Therefore, take a good look at whether these studies could be relevant to your company or organization.